Though the Trump administration continues cracking down on immigration, the effort appears to have little impact on the number of migrant farmworkers arriving in the North State. Thousands, both undocumented and on temporary work visas, are now arriving for the summer picking season. North State Public Radio reporter Adia White looks at how they’re able to make a home here, before leaving again in the fall.

***

It’s the start of the picking season, and the population of Sutter County spikes as thousands of migrant farmworkers come to the area to work.

Take Maria Flores, for example. She is from Michoacan in Mexico, but her family comes to Marysville every summer to help in the the orchards.

She says that she’s been making the trip for eleven years. This arrangement can be a win-win: farms that don’t need as many workers year-round rely on the extra labor for the picking season. But the challenge is housing all the families who are only here for a season. California’s Department of Housing and Community Development has tried to come up with a solution.

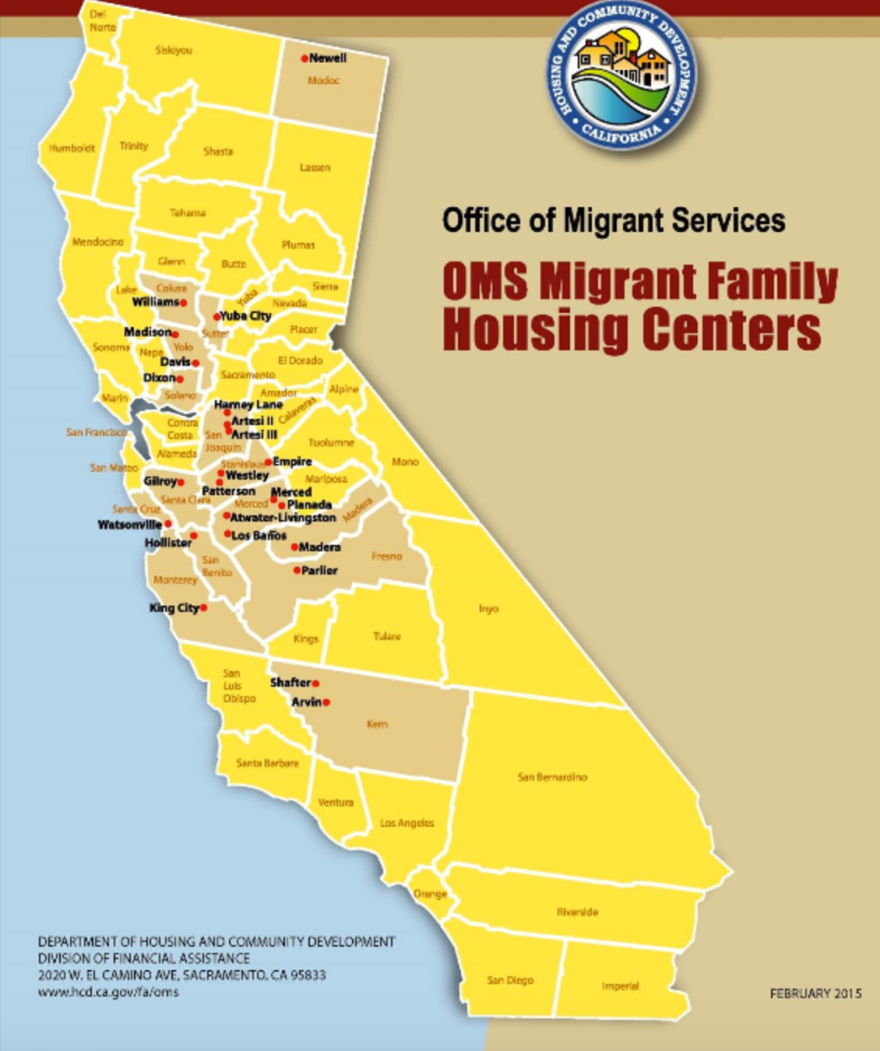

The state runs 24 migrant housing centers across California with three north of Yuba City. There’s one in Colusa, one in Modoc and one in Marysville. The Marysville complex, where Maria lives, has 78 family apartments.

And this subsidized complex is why her family has been able to keep coming to Marysville year after year.

She says the rent everywhere else is expensive, and that she hopes it doesn’t go up or she won’t be able to live in the area.

It’s only a few hundred dollars for a two-bedroom, including utilities. But you have to prove you’re a migrant farmworker to qualify. That means demonstrating that 50 percent of your income comes from farmwork, and that you’ve lived at least 50 miles away from the center for three months or more before moving in.

It may sound strict, but there are far more people that fit that criteria than there are units available.

Gus Buccero is the complex’s housing manager.

“This is the first year that it has been full since day one,” he said. “Before, it took 30 days to fill. This year on day one, we saw full occupancy and a waiting list.”

That waiting list, he says, still has 24 people on it.

“The problem is rents are outpacing incomes,” he says.

It’s near impossible to get an exact count on how many migrant farmworkers are homeless or living in substandard conditions, but the numbers do show that there are significantly more migrant farmworkers here than there are housing options that they can afford.

In their 2014 general plan, Sutter County roughly estimates that nearly half of the farmworker population in rural Sutter is without adequate housing options. Eileen Jacobs is a lawyer at the California Rural Legal Aid Society. She says that in her 13 years representing tenants in the area, she sees many farmworkers trying to make due in barely habitable conditions.

“Some people call it unconventional housing,” she says. “I think that unconventional is a generous word when it’s used to describe a field or a car or a truck or a tarp or the river bottoms, old motels where they are doubled or tripled, sometimes 10 to a room.”

Jacobs says that another way many find housing is through labor contractors, who often run camps to house the workers they recruit. These camps can be a great option. But there are also countless that are unlicensed and provide dismal living conditions

“HCD has had their state budget starved so they cannot do code enforcement on a complaint-based basis and they are not regularly inspecting,” Jacobs says.

And if the Department of Housing and Community Development were to do regular inspections anywhere, one would think it would be Sutter County.

The area has a dark past. In the ’70s, a labor contractor responsible for hiring migrants and housing them murdered 25 people, nearly all the migrant farmworkers he employed.

Not to imply that inspections could have prevented that, but the incident does demonstrate the vulnerability of the population, who are often new to the area or don’t speak the language.

Needless to say, when you ask the residents at the state-run housing in Marysville, seguro, safe, is what they all say to describe the place.

Take Portencia, for example. This is her second year coming to the center.

“The houses are clean,” she says. “It’s nice here. I feel secure.”

And having enough livable and affordable housing for farmworkers isn’t just important for the them. It ensures that farms can rely on that seasonal workforce, and it helps protect the agricultural-based economy crucial to the region.